Wednesday, September 05, 2007

My Blog Has Moved!

Due to the terms of my contract, I've had to change the name of my blog (so that they can own the new name) - and so the new blog is named Surveillance State. The new blog is located at:

http://www.cnet.com/surveillance-state/

For the most part, the blog will remain the same - still a focus on security and privacy, with a bit of amateur legal analysis thrown in for fun - although expect slightly more frequent posting (3x per week or so).

I've already posted a couple articles this week - while we were still getting all the kinks worked out of the system: An analysis of Comcast's BitTorrent filtering (and the laws they may be breaking in doing so), and today a post on Apple's iPod Touch (and the fact Steve Jobs won't be able to blame AT&T for keeping the platform closed).

I hope you'll all follow me over to CNET.

Thursday, July 19, 2007

Airport Security x 3

This blog post is likely to be the last until September, as I'll be leaving Munich next week, and will spend the entire month of August backpacking in India. I expect to have email access in Ladakh, and I doubt if there will be decent Internet in the remote villages in the Parvati Valley - at least, there wasn't any when I visited last year.

Today's blog post is in three parts, all related to airport security: The end of my legal troubles, the successful publication of my airport security research paper, and a brief writeup of my recent experience going through British airport security.

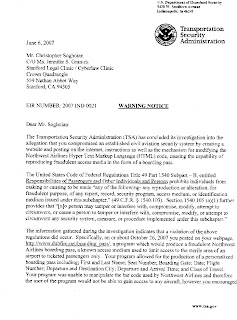

I received word from my awesome pro-bono legal counsel, Jennifer Granick, that TSA has wrapped up their investigation, and will not be filing civil charges against me. The FBI dropped their investigation in November last year. It looks like the entire affair is now over.

Ten months after the FBI strong-armed my ISP into taking down my website (as well as ransacking my home, and making off with my computers and passports), the flaws that I highlighted are still exploitable, and have not been fixed. The reimplementation of my boarding pass generator by "John Adams" (that was first released on November 1 2006) also remains online.

In addition to the help of super-lawyers Jennifer Granick and Steve Braga, I received an outpouring of support from around the world, from the students, faculty and staff at Indiana University, and from my friends, family and loved ones.

One particular friend provided me with a place to stay the night the FBI visited, and had it not been for their instance that I come with them, I would have been at home when the G-Men broke in at 2AM, guns drawn. To this person in particular as well as everyone else who helped out, I am eternally grateful.

Security research is typically a two part process: You break something, and then you fix it. My boarding pass generator and numerous blog-posts highlighting the no-id + no-fly list problem were the first part of the research process. A newly released academic paper fixing the flaws is the second part.

I am proud to announce that my paper "Insecure Flight: Broken Boarding Passes and Ineffective Terrorist Watch Lists" has been accepted for publication by the IDMAN 07 working conference, where I'll also be presenting it in Rotterdam, Netherlands in October.

Bruce Schneier, Senator Schumer, and others did a great job in highlighting the fake/modifiable boarding pass problem years before I built my hullabaloo causing website. However, no academic has yet written about this. My paper fully explores the interesting combination of the ability to fly without ID, and the government's insistence on maintaining a no-fly list. I have personally flown without ID over 12 times, and I do not believe that anyone else has really written about the fact that this essentially neutralizes the no-fly list. I also present a new physical denial of service attack against the TSA passenger screening system.

It is important to note that I do not take a position on the no-fly list in the paper. The US government has spent over $250 million dollars on implementing the list. The paper thus explores methods to effectively enforce it. The paper presents a technical solution to the problem (digitally signed boarding passes), which will enable TSA staff to instantly learn if a pass is valid or not, or if it has been tampered with, as well as stopping all other known attacks.

Were the airlines in the US willing to check the ID of each passenger before they board a flight - something they did right after 9/11 - my technical solution wouldn't be necessary. 100% effective enforcement of the no-fly list is only possible when airlines check all IDs at the gate, and when the US government takes away our right to fly without ID.

A pre-publication copy of my paper can be downloaded here.

I was in London two weeks ago to see family. I flew in a few hours after the failed bomb attack, and was watching TV in east London when the idiots tried to drive a flaming jeep into Glasgow airport.

I flew back to Germany a couple days later, and in spite of the fact that I had to get up at 4AM for my flight, I paid close attention to the security procedures in place at Stansted Airport.

- There is now an unwritten but enforced rule banning large umbrellas. If it can't fit in a carry on bag, you're forbidden to take it through security. British airport security staff thus seized my golf-umbrella.

- Just as in the US, the British consider hummus to be a liquid. I took the top off the container, held it upside down, thus demonstrating that it would not pour out, but the screener insisted that I give it up. The supervisor on duty did at least let me sit on one of the bag-searching tables, with people's bags being searched on both sides of me. Thus, under the watchful corner-of-the-eye of her security staff, I ate all the hummus and pita bread I had brought with me as my lunch. The supervisor even went out of her way to bring me an unrequested cup of water . I can't imagine TSA staff doing this.

- Print at home boarding passes with the airline Easyjet contain a computer-readable barcode. This barcode is read by airport security screening staff, before you even enter the metal detector/x-ray line. I'm not sure what happens if the barcode doesn't find a match - but I did observe that my name came up on the screen, which the security staff member then compared to my ID. This means that if your name is not associated with a paid ticket in the reservation system, you will not even gain access to the security screening area. Quite impressive.

- Once Easyjet staff began boarding, they looked up every passenger's name in the reservation system and checked it against an ID before letting the passenger onto the airplane. No passport, no entry.

Comparing US domestic flight security to European flight is not 100% fair. You do not need to show ID to travel within the US, and except for a few select situations, you cannot be forced to show ID in the US. Europeans do not have this right, and as the individual European countries are much smaller than the US, you are essentially always crossing some international border when you fly.

US airlines somehow managed to get the government to let them stop asking for ID at the gate - after they complained about the labor costs and delays the process introduced to the flight-boarding process.

Nonsense.

If Easyjet, a no-frills airline that won't even give you a free glass of water, can ask passengers for ID and somehow manage to turn a profit, as well as get their flights off in a reasonable amount of time, then the US airlines are not telling the truth.

I lived in the UK when the IRA, through the use of bombs placed in train-station rubbish bins, forced the authorities to remove every trash can from train and tube-stations in London.

While the Israelis get a lot of credit for their airport security skills - as others have pointed out before me, Israel is small, and doesn't have many flights in or out. London's Heathrow is one of, if not the the busiest airport in the world. The British have had this airport security thing figured out for years. If the US government is serious about enforcing the no-fly list, they should learn a thing or two from the Brits, and force all airlines to check passengers' ID against a computerized reservation system record at the gate.

The flip side of course, is that if the US government finally accepts that the no-fly list is a pointless waste of money, then that money can be spent on more important things - like training TSA staff to actually find the weapons and bombs that currently seem to miss, again and again.

Monday, July 09, 2007

Astroglide Data Loss Could Result In $18 Million Fine

[scroll way down for a spreadsheet containing numbers of Astroglide requests per state]

Executive Summary

In April 2007, Biofilm Inc. accidentally published on the Internet the names and addresses of over 200,000 customers who had requested a free sample of their popular sex lubricant Astroglide. This blog post highlights the fact that the leaked data could serve as highly effective bait for targeted phishing attacks and other kinds of scams. A full breakdown of numbers of requests for each state are released. These numbers are then used to estimate potential fines against Biofilm should state Attorneys General wish to get involved.

Introduction

Privacy is a strange beast. It is one of our "rights" least well defined and protected by the law. The U. S. Constitution contains no express right to privacy. Likewise, data protection is something that has yet to be properly addressed by US law.

Consumers regularly surrender their personal information to random strangers in return for t-shirts and teddy bears as credit card sign-up bonuses. Similarly, many consumers permit the tracking of individual items in their supermarket purchases by companies in return for modest discounts or "points" through loyalty schemes.

Data protection and privacy become far more important when they relate to personal and sexual information. Most consumers would probably be more concerned about someone else gaining access to the order info for ther their Good Vibrations (an online seller of marital aids) account than for their past book purchases from Amazon.

Likewise, when Congress rushed to pass extremely pro-privacy restrictions on the release of video-rental records in 1988, it was not because they were concerned about tabloid journalists learning how many times a particular Senator had rented Citizen Kane.

A Slippery Problem

The main subject of this blog post relates to a data loss/accidental release by a California company named Biofilm, Inc. They are the makers of Astroglide, a popular sexual lubricant.

For most of April 2007, a database of names and addresses of individuals who had requested free samples of Astroglide was inadvertently left unprotected on the company's website. In addition to random visitors being able to access the database, Google's search engine spider software made copies of the database - cached copies of which continued to be available online from Google's site for more than a week after Astroglide removed the data from their own website.

Within hours of Wired News picking up the Astroglide story, fellow Indiana University PhD student Sid Stamm and I began frantically downloading all the data from Google's cache. The leaked Astroglide database contains the names and addresses of individuals who requested a samples between 2003 to 2007. With a bit of effort to clean out duplicate entries, we soon had a database of just over two-hundred thousand unique names and addresses.

I've been struggling to come up with an interesting, useful and ethical way to use this data. While the obvious Yahoo Maps mashup is amusing (and scarily mind blowing), it's just not fair to the people who gave Astroglide their data in good faith. They do not deserve to have their privacy violated and abused more than they have already suffered. The screenshot posted at the top of this blog post is real - but out of respect to the people in the database, I will not be putting the mashup online.

More Than Just Embarassment

There is almost no chance that the Astroglide data could be used to steal someone's identity. Unfortunately, the data loss laws passed by the various states only really have identity theft in mind, and so they did not kick-in in this incident. This is primarily due to the fact that the data that was exposed does not match the strict definition of PII (personally identifiable information), as in this case, no social security, credit card or other account numbers were revealed.

Adam Shostack is quite vocal about his belief that data breaches/data loss incidents are not just about identity theft. He writes that "[Data Breaches] are about honesty about a commitment that an organization has made while collecting data, and a failure to meet that commitment."

My immediate reaction and concern when reading about the Astroglide incident was, "how embarrassing." Yes, it would be quite unpleasant for the people in the database if their colleagues, friends and attendees of their church learned that they had requested a sexual lubricant. Having this information come up in a Google search for the person's name could even pose a problem during some job interviews.

The Astroglide incident is bigger than just the issue of embarrassment. The smallest bit of information about an individual can serve as a vehicle for targeted phishing and other kinds of fraud. I discussed this with Prof. Markus Jakobsson and he came up with two fantastic examples of scams that could use this data.

- A version of the spanish lottery scam with a spear phishing touch: A would-be phisher could send a postcard to each name on the list, advising them that since they are fans of the product, they were enrolled in an online lottery - and that they have won. All that they need to do is to go online to claim their winnings.

- A class action version of the Nigerian 419 scam: A swindler could send a postcard to victims, notifying them of the data loss, and stating that they have been invited to join a class action lawsuit against Biofilm/Astrolide. The victim would be told that they will receive several hundred dollars as part of the settlement, and all that they need to do to claim their share is to fill out the postcard with their banking details and send it off.

These and other similar attacks would be much easier (and cheaper for the attacker) if they could be conducted by email. Turning each of the 200,000 names addresses into a valid email address is not an easy task - thankfully. This at least raises the cost of any attempted scam to the cost of a stamp for each potential victim.

A few months ago, I highlighted an incident at Indiana University where phishers were able to obtain a list of valid email addresses for IU students. They were then able to use this list, which consisted solely of users' names and email addresses to launch a highly successful spear phishing attack against the IU Credit Union.

Likewise, my colleagues in the Stop Phishing Research Group at Indiana University have conducted several targeted phishing studies that have clearly demonstrated the impact that of even the smallest bit of accurate information on a user can have on the effectiveness of a phishing attack. Simply put, Anything that is known about people can be used to win their trust. Such insights are used to improve consumer education in the recent effort www.SecurityCartoon.com.

I suspect that most phishing attacks against credit unions and small regional banks already involve some form of data breach/loss. The economics of phishing simply do not add up otherwise - a phisher would be far better off claiming to be Citibank/Chase if they are sending out an email to 3 million randomly collected email addresses. I predict that we'll see a lot more of these kinds of phishing attacks. Although, due to the fact that notification won't be required in data loss incidents where social security or credit card numbers are not lost, the public will not be told how the phishers got their target list.

Phishers are constantly evolving their techniques. As in-browser anti-phishing technology becomes the norm, and spam filters mature, we will likely see a shift towards more targeted phishing. These attacks involve far less email messages, and are thus likely to better stay below the radar of the anti-phishing blacklist teams at Google, Microsoft and Phishtank. While data loss/breach incidents involving social security numbers of course pose a identity theft risk - the risk of this information being used for phishing and other scam attacks is currently being completely overlooked.

The solution to this, of course, is to amend the data breach/loss notification laws to apply when any customer information is lost or released to unauthorized parties. Companies will fight this, citing the high cost of notification and a desire to avoid needlessly worrying their customers. The laws will stay the same, and phishers will laugh all the way to the bank.

Could Biofilm/Astroglide be fined?

Contrast the Astroglide data loss to a completely separate yet similar incident:

Between August and November of 2002, the order information (name, address, items purchased) for over 560 customers was available to any curious visitor on the website of American underwear retailer Victoria's Secret. This was due to a web security snafu, which was soon fixed after it was reported. The following year, New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer negotiated a settlement with Victoria's Secret, in which the company agreed to pay the state of New York $50,000 as well as notifying each customer whose data was inadvertently made available online. The New York Times had a full write up of the story online.

I think it's really useful to compare the two different cases. In both, data was accidentally put on the Internet. Neither dataset contained credit card numbers, social security numbers, or what we would usually think of as PII. As such, the various state data breach/loss laws didn't kick in.

However, while the data lost (name and address) wasn't particularly sensitive - after all, in many cases, it can be looked up in the phone book - it is the combination of that data with a highly sensitive and sexual product which would give the average consumer a legitimate cause for concern.

Victoria's Secret agreed to notify every customer whose data was accidentally put online. Astroglide has not told a single customer. Victoria's secret agreed to pay $50,000 to the state of NY for about 560 customers, although only 26 of them were actually NY residents. Astroglide has not paid a single penny to any state as a result of this incident.

I think Biofilm should be held accountable for the accidental publication of the names and addresses of 200,000 customers. To remedy this, I have spent quite a bit of time over the past couple weeks filing complaints with numerous state Attorneys General, including the notoriously pro-privacy AGs in California and New York. I have filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission. A few hundred overseas consumers tried to get Biofilm to send them a sample by airmail. Thus, I'm working with The Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic to file a complaint with the appropriate Canadian authorities. I've also already filed complaints with the data protection agencies in the UK, Ireland, Belgium, The Netherlands and Finland.

A wise lawyer has informed me that the ultimate way to kickstart things is to find a California resident victim, and have that person file an action under CA Business & Professional Code 17-200. My name is not in the database and I do not live in California. Furthermore, I do not feel that is would be ethical to go through the list of 17 thousand California residents, looking them up in google, hopefully finding an email address, and then contacting those individuals to ask them to file a complaint. Thus, as much as I'd like to get a CA Business & Professional code complaint filed against Biofilm, my hands are currently tied.

There are two ways to judge the cost of data loss per customer for Victoria's Secret. $50,000 divided by 26 New York residents equals approximately $1925 per customer. However, given that no other state fined Victoria's Secret, it is probably safer to divide the $50,000 fine by all 560 customers, which gives us a fine of approximately $90 per customer.

Using that $90 per customer figure, I decided to figure out how large of a fine Astroglide could potentially face, assuming of course, that one or more state Attorneys General began investigating.

I pulled per-state stats from the database - which are broad enough that I feel confident that I can release them without putting any individual user's privacy at risk. Using state population estimates from the US Census Bureau, I was also able to calculate a ratio for the number of people in each state per Astroglide request. As much as I was hoping that KY (Kentucky) would win - I could already visualize the Fark headline - North Dakota won, with one Astroglide sample request per 908 state residents. New Mexico came in "last" with one request per 2656 state residents. Analysis of what these numbers actually mean is an exercise best left to the reader.

While it may not be realistic to expect Biofilm to pay $18 million in fines, it's quite surprising that they've been able to get away without even having to notify all of their customers. My hope is that by putting this limited bit of information online, I can hopefully start a debate on this issue.

Conclusion

This blog post will hopefully raise the profile of the Astroglide data loss incident, which unfortunately disappeared from the headlines after a day or two without Biofilm being held accountable for the massive breach of customer trust. It should also highlight the fact that once data has been cached by Google, putting the proverbial genie back in the bottle is next to impossible. If two PhD students can pull a copy of the database from Google's servers, so can malicious parties, including would-be phishers. It is perfectly reasonable to expect that multiple copies of the database were downloaded before Google heeded Biofilm's request, a few days later, and removed the data from its cache servers. Likewise, it is quite reasonable to expect that at least one of the downloaders has criminal intentions - or at least a willingness to sell the data on to others.

Consumers in the database face more than just embarrassment. To minimize the risk associated with phishing and other scam attacks, Biofilm should be forced to notify each of the 200,000 + exposed individuals. The take home lesson from all of this, is that these kinds of data loss incidents will continue to occur in the future and it's highly unlikely that consumers will be told. Existing data breach/data loss laws have been narrowly focused to target the threat of identity theft, a noble goal, but by no means the only threat that consumers face. These laws should be amended to correct this problem. Consumers have a right to be told whenever their information is inadvertently released to unauthorized parties.

Wednesday, July 04, 2007

FOIA Results: No evidence of Direct US Involvement in Pirate Bay Takendown

One of the perks of graduate school, is that as an academic researcher working in the public interest, I'm eligible for fee waivers for all of my FOIA requests. I can request whatever I want, and as along as it's reasonably related to my research, I'm spared the 10 cents per page photocopy charges + hourly fees for government employee research time.

FOIA requests take time. However, I've filed several over the past year, with some success, and some rejections. Using the Indiana State equivalent of FOIA a couple months ago, I was able to gain quite a bit of information on a phishing attack that targeted university students the year before. I've also successfully used it to get police reports from the Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority regarding a potentially illegal incident where a police officer compelled me to show my drivers license after I attempted to assert my right to fly without ID.

On May 31 2006, Swedish law enforcement raided and seized servers used by the popular bit torrent tracker/website The Pirate Bay. Press reports at the time claimed that the raid was a result of significant US pressure. Some reports hinted at more direct involvement by the US government.

Thus, in September of 2006, the first FOIA request I filed was to the US State Department to get a copy of any documents relating to US knowledge of or involvement in the raid on The Pirate Bay.

I recently got 27 pages of documents, mostly uncensored, back from the State Department. While it's possible that they're withholding some information, from the documents that they've given me, it looks like the Swedish authorities organized the raid on their own. The US government was clearly putting strong pressure on the Swedes, but it does not appear as though the US government had advanced notice of, or any direct involvement in the raid.

All 27 pages of documents have been scanned and placed online.

Happy birthday FOIA!

Thursday, June 28, 2007

Facebook Cares More About Privacy Than Security

Facebook's head privacy engineer, Nico Vera, seems to reside in some sort of Cheney-ish undisclosed location: He's not listed in the corporate phone directory, has instructed Facebook's receptionist to not accept outside calls, and did not reply to my intra-Facebook email.

Luckily - Facebook's PR people are a bit more responsive. It's amazing what a few calls from journalists, and a Boing Boing blog post can do to motivate a company to act quickly.

I tried a few sample searches, and can confirm that Facebook has indeed fixed the bug. My days of searching for private profiles of Facebook users under the age of 21 who list beer or marijuana as one of their interests is over. It's a shame too, as it made for a great "be careful with your information online" example when I lecture undergrads.

While Facebook offers a fantastic level of privacy controls for users, in this case, they clearly erred. Many users had gone to the effort to make their profiles private - and as such, Facebook should have assumed that they would also not wish for their profile information to be data mined through a number of iterative searches. Opt-out privacy is not the way to go - especially for users who have already communicated their intent to have their data be restricted to a small group of friends.

Facebook's engineers fixed the problem within 36 hours of the initial blog post going live, and within a business day of the blog post being linked to from Boing Boing. This rapid response is fantastic, and the Facebook team should be proud of the way they demonstrated their commitment to protecting users' private information.

Contrast this, however, to the Firefox extension vulnerability I made public one month ago. I first notified the Facebook team of the flaw in their Facebook Toolbar product over 2 months ago, on April 21, while the story hit the news a month later on May 30th.

As of this morning, it looks like Facebook has still not fixed their toolbar - such that it continues to seek and download updates from an unauthenticated and insecure server (http://developers.facebook.com/toolbar/updates.rdf). Google and Yahoo who fixed the same problem in their products within a few days.

Yes - being able to quickly and effortlessly find out someones sexuality, religion and drug of choice (when they believe that their profile is private) is a major problem. It's far more serious than the chance that someone in an Internet cafe will take over your laptop - which is probably why Facebook rushed to fix the privacy problem so quickly. However, the security flaw in the Facebook toolbar remains an unresolved issue, and there is simply no excuse for them to wait two months to fix this vulnerability.

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

Go Fish: Is Facebook Violating European Data Protection Rules?

Executive Summary

Using nothing more complex than an advanced search on Facebook's website, an interested person can learn extremely private pieces of information (sexuality, political leanings, religion) that are stored within another user's private Facebook profile.

Users of Facebook can modify the privacy settings for their profile. This will restrict the public viewing and only permit a person's immediate friends to view their profile. While Facebook does allow users to control their profile's existence in search queries, this second preference is not automatically set when a user makes their profile private - and thus many users do not know to do so.

Users cannot be expected to know that the contents of their private profiles can be mined via searches, and thus, very few do set the search permissions associated with their profile.

It is clear however that users intend for their profiles to not be public. A large number of users have gone to the effort to restrict who can view their profiles, but many, unfortunately, remain exposed to a trivial attack.

The Attack

The attack is very simple. For a specific target, one must simply issue an advanced query for the user's name, and any attribute of the profile that one wishes to search.

For example, I've created a new profile in the name of "Chris Privacy Soghoian", who is socially conservative, a Catholic and lives in London, England. His profile privacy has been set so that only his friends may see his profile. Random strangers should not be able to learn anything about the profile - they cannot click on it or view the profile's information.

By issuing an advanced search request for Name: "Chris Privacy Soghoian" and Religion: "Christian - Catholic", one can learn if the profile for that user has listed Catholicism as his religion. Note: To be able to find this profile, you need to be signed in to a facebook account that is a member of the London, UK network. Anyone can join this and other geography based networks, but you must do so first before searching.

If a profile is returned for the search terms requested, one can be sure that the user in question has the relevant information in his profile. It is also easy to see that the profile has been set to private, as the user's name is in black un-clickable text.

Likewise, a similar search for Chris Privacy Soghoian/Buddhist would come back with no results.

This shows how easy it is to learn confidential information that users believe that random strangers cannot learn when they have set their profile to be private/friends-only.

This attack is very similar to the children's game Go Fish. It won't tell you the contents of a profile, but it will provide you with positive or negative confirmation if you know what you're looking for.

So What's The Big Deal?

I originally wrote about this attack in September of last year. I was mainly focused then with finding out the names of students who admitted (in their private profiles) to working at the local strip clubs, and of those students under the age of 21 who listed beer and alcohol in their hobbies.

Stripping and alcohol are interesting enough - and they prove to be fantastic examples when I use them as a demo of "why you need to be careful on Facebook" when lecturing students in my department. However, in focusing on things that would amuse and scare undergrads, I completely missed the hot potato: Sexuality and Religion.

I attended the Privacy Enhancing Technologies workshop last week. While there, I mentioned the Facebook attack to several attendees. A couple of the Europeans were shocked, and told me that Facebook was almost certainly running afoul of a number of European data protection rules.

Privacy is not something that the US government really cares too much - unless of course, you are a politician or supreme court nominee - in which case, they'll pass watertight legislation to protect your ahem "adult" movie rental records.

The Europeans do care about privacy. Sexuality and Religion are bits of information that they consider to be highly sensitive.. and thus, my little go fish attack is now suddenly a lot more important than it was before. Facebook's default search privacy policies may violate European Data Protection rules.

Sample Queries

The following searches will only work if you are signed in to facebook. It is easy to create an account - anyone can make one, and all that you need is a valid email address.

The queries will search everyone within all of your networks - which will include any university/school/employer that you select, as well as a geographic group. There is no proof required of your current location, and so if you wish to search for everyone in France, it's trivial to make a new account/profile located there.

All women interested in women.

All men interested in men.

All Christian men interested in other men.

All Hindu men interested in other men.

All Muslim men interested in other men.

All Jewish men interested in other men.

All Christian women interested in other women.

All Hindu women interested in other women.

All Muslim women interested in other women.

All Jewish women interested in other women.

Clicking on any one of these - at least when you've joined a decent sized network - will return a large group of people - a fairly significant number of whom have profiles that are marked private, which you cannot click on or learn more about. However, by merely appearing in the list of returned profiles, you can be sure that the person's private profile contains information that matches the search terms. This is a problem.

Fixing The Problem

Facebook's privacy policy essentially states that Facebook is not responsible in any case where a user is able to obtain private information about someone else: Although we allow you to set privacy options that limit access to your pages, please be aware that no security measures are perfect or impenetrable... Therefore, we cannot and do not guarantee that User Content you post on the Site will not be viewed by unauthorized persons. We are not responsible for circumvention of any privacy settings or security measures contained on the Site.

Facebook should be commended for the fact that they have implemented a simple technical solution to the problem. Users can control their search privacy settings - and thus control who can see their profile when searches are issued on the facebook site. This feature did not exist when I first described the vulnerability last year.

The problem is that users must opt-in to this more restrictive privacy setting. Users who have gone to the effort of marking their profiles as private (so that others cannot view them) are not clearly warned that other users may be able to learn bits of information by issuing highly specific search queries. Users should not be expected to know or even understand this.

Facebook should change their defaults, and automatically restrict the profile search settings for any user who makes their profile private. Those users who wished to permit strangers to find them in a search could opt in and modify this setting themselves.

Disclosure

Normally, for something like this, I would follow the norms of responsible disclosure (as I did last month with Firefox/Google) and give Facebook advanced notice of my planned release. However, since I first announced this attack on my blog last September, it doesn't really make sense to try and keep it secret. This post doesn't announce anything new - it merely restates the previously described attack in clearer language, provides a couple screenshots and some sample queries that people can click on.

Parsing Privacy Policies: Is OpenDNS logging data forever?

OpenDNS is the frequent darling of the security press. The very same journalists frequently pummel Google (and rightly so) for their lackluster approach to customer privacy.

Last month, OpenDNS's CEO started throwing dirt at Google for their pretty shameful keyword hijacking advertisement deal with Dell and others.

In a separate matter, Google recently adjusted its logging policy (although not nearly enough), after getting smacked around in a PR dust-up initiated by Privacy International. Given the fact that David Ulevitch and OpenDNS were willing to take such an admirable public stand against Google, I decided to look into OpenDNS's own privacy and logging policies - to see how they themselves fare against the Big G.

The most relevant portions of OpenDNS's privacy policy include:

OpenDNS's DNS service collects non-personally-identifying information such as the date and time of each DNS request and the domain name requested.

OpenDNS also collects potentially personally-identifying information like Internet Protocol (IP) addresses of website visitors and IP addresses from which DNS requests are made. For its DNS services, OpenDNS is storing IP addresses temporarily to monitor and improve our quality of service.

In addition, we may combine non-personally-identifiable information with personally-identifiable information in a manner that enables us to attribute website and DNS service usage to an individual customer's computer or network.

Other than to its employees, contractors and affiliated organizations, as described above, OpenDNS discloses potentially personally-identifying and personally-identifying information only when required to do so by law, court order, or when OpenDNS believes in good faith that disclosure is reasonably necessary to protect the property or rights of OpenDNS, third parties or the public at large.

What does this mean?

OpenDNS is logging information on all DNS requests received by their servers. They log the IP address that initiated each request. Thus, OpenDNS knows and stores the fact that at 11:10PM on Friday the 22nd of June, someone at the network address of some-user-in-washington-dc.comcast.com visited www.thepiratebay.org

OpenDNS logs data on every single unique domain name that you visit. They know that you have visited www.ilikeburritos.com and sometimes.ilikeburritos.com, but they don't have any info on which specific webpages in those domains that you visit. This is still a huge amount of information - more, possibly, than Google knows.

OpenDNS keeps this information for a "temporary," yet undefined period of time. Unlike Google, who promise to anonymize the data after a set period of time, it does not look like OpenDNS makes any attempt to anonymize any of their logs.

It does not look like OpenDNS has any kind of public log deletion policy, and thus they could still be storing log data years after the queries were sent to their servers.

This information could be requested by law enforcement, the RIAA, or an angry spouse in a divorce case. These would all be legal instances in which the courts could compel OpenDNS to reveal data on customers. The only way to avoid having 8 year old DNS requests showing up in a custody dispute would be for OpenDNS to announce and enforce a data logging and log deletion policy.

What can you do?

While OpenDNS is not perfect, they are probably still better than your average mega-corporate ISP. Some ISPs already seem to be selling data on which websites customers visit. Likewise, AT&T has quite thoroughly sold its customers out to the RIAA and MPAA.

Instead, the best thing to do is to write to Dave Ulevitch/OpenDNS (david [at]opendns [dot] com) and ask him to revise/create a data deletion and anonymization policy.

Sunday, June 17, 2007

An Emotional Blackmail Takedown: Remove The Podcast, Or We Shoot This Puppy

After the FBI raided my house last year, its fair to say that I've become a little bit more cautious. It's not to say that I'm not pursuing the same kinds of projects, it's just that I find out what my legal risks are before I go public. One interesting project that I've been working on has been stalled for the last few months, as my professor and I wait for a sign-off from both the Indiana University counsel's office, as well as a pro-bono outside counsel the nice folks at the EFF were able to put me in touch with. In that project, there are a number of uncertain legal risks, and it may upset some very powerful people - hence the caution.

Which is why, with this unofficial podcast, I made sure to check out my legal options before I put it online. Trespass to chattel - No problem. Copyright infringement - No problem. Deep linking - Probably no problem.

In the event that I got a proper takedown letter written by a lawyer, I felt that I was on really solid ground. What I did not plan for, was an emotional blackmail takedown that made me feel guilty. In hindsight, I suppose I should have predicted it - as it was the same reasonable, and non-heavy handed approach TAL took last year when two other guys setup podcasts.

The message they've given me is this: If you don't remove the podcast, we'll have to spend our limited resources (including the $20 that you donated last week) to pay lawyers to harass you.

I love This American Life. I look forward to a new episode every week, and I don't want to do anything that causes them to pull financial resources away from production.

TAL recently had a podcasting fund-drive, to pay for the $108k in yearly bandwidth costs for their approx 300,000 weekly downloads. In less than three weeks, they raised over $110k - solely by asking for money on their website, and in a request added to the weekly podcast.

Personally, I think that spending over $100k of listener donated money on bandwidth is an almost criminal waste of funds, when archive.org (who also provides free podcasting for Democracy Now) is more than willing to provide free bandwidth.

That massive waste of financial resources, is sadly, not under my control. What is under my control, on the other hand, is if TAL will have to spend several thousand dollars on legal bills - only to probably find out that everything that I've done is above board. This additional waste of resources is not something I would want to shoulder the responsibility for. In addition to wanting to do the right thing - both my girlfriend and my best friend are also fans of TAL, and I'm guessing that they'd give me a good kicking were I not to back down on this one.

Furthermore, I'll be traveling to and from the Privacy Enhancing Technologies workshop in Ottawa, Canada for the next 6 days. I'm really not comfortable with the idea that I'll be passing through US Customs + TSA with the possibility of a cease and desist sent by a US government funded group hanging over my head.

So - effective immediately, the podcast feeds come down. However, given its effectiveness, and lack of involvement of lawyers, I'm posting the letter I received from Daniel Ash at Chicago Public Radio. I hope that it will perhaps serve as an example to other, more litigation trigger happy organizations. Although, somehow I suspect that an appeal to conscience may not be as effective when the group has been voted the worst company in America.

Christopher,

First of all, thanks for your recent donation to support our bandwidth costs for This American Life. It helped make our online pledge drive a great success.

I am also writing because it has come to our attention that you have set up unofficial, “takedown resistant” podcasts of This American Life. We kindly request that you end this practice immediately.

On your blog, you go into impressive detail outlining the gray areas of the law in which you have ensconced your podcasts. Rather than first turning to our lawyers (at a high cost to our member-supported public radio station) to request that they look into the legality of what you’re doing, we’d like to ask nicely for your cooperation. And even if it turns out that you have found some podcasting equivalent to an off-shore tax shelter, we would still request that you stop. Here’s why:

As you mention, radio must adapt to the digital age. Our content is no longer tied to a single delivery system—that old-school box on your kitchen counter. Now, a number of much smaller, new-skool boxes enable you to take media content wherever you like and to consume it whenever you want.

Adapting to these changes is not always a smooth process. As you noted, we’ve been working hard to find the right digital delivery model for This American Life. For years, we did indeed have an exclusive contract with Audible that prevented us from offering a free podcast. Better late than never, we finally renegotiated that deal and launched a free podcast. Yes, it does have some limitations, chiefly that only one episode—our most recent broadcast—is available at any time. But once you’ve downloaded it, it’s yours to keep. And our archives, more than 300 episodes that span 13 years, are available for purchase at just $0.95 an episode.

In your blog, you suggest a different business model:

"The nicer, and smarter approach (in my humble opinion) would be to ditch the paid podcasting model, allow other organizations to host the TAL podcasts, and thus do away with that nasty bandwidth bill. In three weeks of fundraising, they were able to raise over $110k - more than enough to cover the costs of their 300,000 podcast downloads per week. If bandwidth were provided by others for free, this money could instead go towards TAL's other operating costs - and thus make up for the loss of the iTunes/audible.com revenue stream."

It’s not a bad idea—and one that we’re considering as the media industry as a whole works toward getting better metrics. We’re also watching advances in peer-to-peer technology; at some point, that might be a more plausible alternative for reliable delivery of our content. But these decisions aren’t yours to make.

We want to share This American Life with as many people as possible. But it’s also a very expensive show to produce. In order to offset our costs, we work to attract sponsorships and to develop business partners. Our current contracts are premised on a specific distribution model: namely, a weekly radio broadcast and free podcast, along with a minimally-priced back catalog. Not only do your podcasts make an end-run around this model, but they have the potential to disturb the already-muddy waters of measuring how many people download and listen to our files.

To recap, this is not a cease-and-desist kind of letter. No lawyers were consulted, and we hope there’s no need to involve them. This is simply a request. We acknowledge that our current business model isn’t perfect. But you have to admit that it’s a whole lot better (and to use your words, “nicer and smarter”) than it was 18 months ago. We want to be nice and smart in our practices, and we intend to continue in that direction as we move forward. But for now, this is where we stand, and it’s not going to change in the immediate future. We won’t ask you to stop what you’re doing for your own, personal enjoyment of the show; but hope you understand the reasoning behind our request that you take down the podcast feeds.

Thanks for your consideration.

Daniel

Daniel O. Ash | Vice President | Strategic Communications | Chicago Public Radio

Friday, June 15, 2007

Can The US government Infringe on Trademark

What is interesting, is that the new section of TSA's website is called "MythBusters". As many of you may know, MythBusters is the name of a hugely popular TV show on the Discovery Channel.

It turns out that Discovery Communications has registered the term MythBusters with the US Trademark office as: Entertainment services in the nature of non-fiction television programming featuring examination of popularly held beliefs and misinformation; information regarding same provided via a global computer network.

Trademark isn't really an area of IP law that I know too much about. My (limited) expertise thus far is mainly in copyright - as it is the area that I'm most likely to get myself in trouble with.

I know that the US government has carved itself a number of exceptions in other areas of the law. For example, the US government cannot commit the tort of "patent infringement" - and instead, merely has to pay "reasonable and entire compensation" to a patent owner for the unauthorized use of a patent.

So - I pose the question to those out there who know more about the law than me:

Can TSA name a section of their website MythBusters (note, even the same capitalization as the TV show) without breaking any laws? TSA's new website provides video footage that examines popularly held beliefs and misinformation, which is then delivered via a global computer network (the Internet).

Is this legit, or did TSA fail to run this by their in-house counsel?

Thursday, June 14, 2007

A Takedown Resistant, Unofficial Podcast Feed for "This American Life"

I get a fair number of hits to this page from people looking for mp3 copies of This American Life episodes.

The short version, is that you can get each episode here: http://audio.thisamericanlife.

The longer explanation can be found here: New location for This American Life Mp3s

The podcast feed that I created, as described in this blog post, was taken down due to a letter sent by This American Life. To read it, go here: An Emotional Blackmail Takedown: Remove The Podcast, Or We Shoot This Puppy

The vanilla feed, which lists the 15 most recent episodes as broadcast by TAL.

A feed of only new episodes, which does not include the reruns as broadcast by TAL.

Please note that this was not done with the permission or consent of NPR, PRI, or the fine folks at This American Life. Show your support, go to the TAL website, and donate 20 bucks.

Introduction

I'm a big fan of the Chicago Public Radio show This American Life (TAL), which is broadcast on many US National Public Radio affiliates nationwide. For some reason, the public radio and TV business (in the US and elsewhere) has not yet figured out this whole Internet thing, and thus many of their online/podcast offerings are less than stellar.

Many young people do not listen to radio anymore. Even when I'm in the US - simply put - if This American Life, Democracy Now, Open Source, Radio Lab and other fantastic radio shows were not available as podcasts - there is no way I'd listen to them. I cannot concentrate on work while listening to an informative radio show, and thus for the most part, streaming them on my computer is just not practical. Instead, they are perfect for the tram ride/walk to work, airplane/bus trips, or walks in the park.

TAL's current business/podcasting model is as follows:

- The latest episode can be downloaded through a podcast feed for free from their website.

- Archived episodes can be streamed online (via a flash player) on their website but not downloaded.

- Listeners wishing to podcast archived episodes must buy them online - from either Apple's iTunes store, or audible.com for 99 cents

This is sub-optimal for many reasons - the most important of which is that I have no desire to enrich Steve Jobs. When I give money to TAL, it is through a direct donation on their website. I do not wish for Apple, or any other middleman to take 30-50%.

TAL has clearly been struggling to find a business plan that works - and are probably contractually bound by their recently renegotiated contract with Audible.com to not allow their back-catalog to be podcasted for free. As Current.org noted, "[t]he barrier to podcasting for years was the longstanding Audible deal. The vendor sold episodes of TAL for $3.95 a pop, barring the show from offering free downloads."

TAL has also recently had a podcasting fund-drive to pay for their yearly bandwidth bill of $108k. I've given them $20, but I can't figure out why they don't just put all of their content on archive.org (as Democracy Now has done), and thus do away with their bandwidth bill completely. Likewise, TAL is extremely popular amongst many tech geek circles - I am sure that a company or two would step up to the plate and give them free bandwidth if they asked.

I suspect that their unwillingness to let others host their media comes from their desire to somehow find a way to preserve their audible.com/iTunes deal. If they are making more than $108k through paid downloads, then perhaps this is a wise choice. The nicer, and smarter approach (in my humble opinion) would be to ditch the paid podcasting model, allow other organizations to host the TAL podcasts, and thus do away with that nasty bandwidth bill. In three weeks of fundraising, they were able to raise over $110k - more than enough to cover the costs of their 300,000 podcast downloads per week. If bandwidth were provided by others for free, this money could instead go towards TAL's other operating costs - and thus make up for the loss of the iTunes/audible.com revenue stream.

When This American Life first moved from Realaudio to MP3 storage of their show archive, the decision seems to be primarily due to issues with Realplayer - and not because they wished to enable listeners to save copies of shows to their machines. While many listeners petitioned TAL for a podcast feed, the show resisted.

Due to the fact that the episodes were being stored as MP3s, it was quite possible for users to download them to their own computers, and for others to create a podcast RSS feed.

In 2006, Jared Benedict and Jon Udell did just this, and made unofficial This American Life podcast feeds. Soon, links appeared in popular websites such as BoingBoing, and shortly after, the TAL webmaster sent a polite takedown request to both gentlemen. Jared sums it up by stating, "we received friendly emails from Ms. Meister, This American Life’s webmaster, making a request to take down the hyperlinks and RSS feeds, or she’d regrettably have to get lawyers involved. While Ms. Meister did miss the mark by accusing us of copyright infringement without a clear understanding of what we were actually doing, or what copyright law allows, she was trying to be polite and friendly which I appreciate."

Subsequently, both men took down their podcast feeds.

Last year, I discovered that TAL has all of their mp3s in one directory, amusingly located at http://audio.thisamericanlife.org/jomamashouse/ismymamashouse/episodenum.mp3. Clearly, their webmaster has a sense of humor.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to give itunes/other podcast clients a directory to download mp3 files from, so a podcast RSS feed is necessary. TAL's official podcast feed only has the most current episode available for download - which doesn't help me when I miss a week, or if I want to load up my iPod for a long journey.

I've learned enough about Internet law at this point to know that website owners are within their rights to get angry if you scrape their website on a regular basis. This comes down to a tort claim of trespass to chattels.

While TAL does provide a podcast RSS feed that I could scrape, I thought it best to avoid downloading data from there, if just to provide a bit of legal distance, and avoid any claim that I was hammering their servers.

Yesterday, I announced and made available a script that pulls data from Google's cache of popular RSS feeds. By using that script, I can be sure that I am not directly accessing TAL's webservers, nor am I increasing the load on their servers (assuming of course, that at least a couple other people using Google Reader to keep up to date with TAL episodes).

Regarding copyright - The content of the episodes, show logos, etc are protected by copyright law. However, episode names, broadcast dates and other info are not. It is for this same reason that one cannot copyright tv schedule listings.

The issue of deep linking (i.e. providing a direct link to a mp3 file on TAL's website) is a legal grey area. The case law here is by no means solid. A few years back, A California judged ruled that, "hyperlinking does not itself involve a violation of the Copyright Act" because "no copying is involved." I am fairly confident that I am on firm ground - since, afterall, the content I am linking to is perfectly legal (thus the DeCSS decision shouldn't apply) and accessible by any user who visits the TAL website and uses their embedded flash mp3 player.

With those legal issues dealt with for the most part, I decided to roll my own.

I've setup two unofficial podcast feeds for This American Life.

The vanilla feed, which lists the 15 most recent episodes as broadcast by TAL.

A feed of only new episodes, which does not include the reruns as broadcast by TAL.

Please note that this was not done with the permission or consent of NPR, PRI, or the fine folks at This American Life. Show your support, go to the TAL website, and donate 20 bucks.

Wednesday, June 13, 2007

Coding Around Trespass To Chattel with Google Feeds API

The day after I published this post in 2007, I published a podcast feed for the NPR radio show This American Life, which used the Google Cache method to build an RSS feed for the popular radio show (TAL only provides the most recent couple shows available to the public for free via a podcast, rather than older shows).

Soon after, I took that podcast feed down after I was directly contacted by someone working for the radio show.

Fast forward five years, and Craigslist is now suing a company called 3Taps for using a method which appears to be surprisingly similar to the technique I described in 2007.

As in 2007, the legal issues surrounding this technique are unclear at best. Eric DeMenthon, the founder of PadMapper, a company using 3Taps data which was also sued by Craigslist told Ars Technica that "Since I'm not actually re-posting the content of the listings, just the facts about the listings, I figured (with legal advice) that there was no real copyright issue there."

Perhaps the courts will finally resolve this interesting legal question.

End update

Check out the RSS/XML cache fetcher here.

Many popular websites now provide RSS/XML feeds for all kinds of data relating to their website. Digg headlines, CNN news, Craigslist for sale items, and millions of blogs.

What happens when you want to build on that data in a way that the website owner didn't plan for, and probably won't approve of?

Since they're providing an RSS feed to the general public, it's unlikely that they can stop you from downloading it. Depending on how you are using the data, they may or may not be able to use copyright law against you. However, they may be able to claim that you're hammering their servers , and thus taking up their resources. In such a situation, normally, if they tell you to stop and you continue, you could be in trouble. This comes under a claim of trespass to chattel - an arcane area of the law that has been used by companies such as Ebay and American Airlines to stop people from scraping their website.

Google has a very popular online RSS reader service, unsurprisingly named Google Reader. Instead of requesting any given website's RSS feed every time one of their millions of users wishes to view this feed in their browser, Google instead serves the user a cached copy. Google's feed crawler ("Feedfetcher") software retrieves feeds from most sites less than once every hour. Some frequently updated sites may be refreshed more often.

The benefits to website owners is clear: Instead of getting hit once every hour by hundreds of thousands of people, they get visited maybe once every hour by Google's software, who then deal with the bandwidth issues involved in getting that data to customers.

Google is even nice enough to modify the user agent string that the feed crawler sends to webservers, to tell website owners exactly how many people have subscribed to the feed.

If you are logged into a Google service (such as Gmail), you can view Google's cached copy of any RSS feed by going to: http://www.google.com/reader/atom/feed/the_feed_you_want

For example, the This American Life podcast feed can be seen by going to: http://www.google.com/reader/atom/feed/http://feeds.thisamericanlife.org/talpodcast

Unfortunately, this cannot be automated with a script - as it requires that you login to a Google Account first. While this can be automated somewhat using the Google provided ClientLogin/AuthSub mechanisms, it would still mean that you'd be scraping the query results. ClientLogin (I believe) also requires that you solve a CAPTCHA, which isn't going to work for a ruby script running on a remote server. Google's terms of service forbid users from automating and scraping data returned from Google queries. If you want to get data from Google with a script, you need to use one of their APIs.

Luckily - Google recently announced a AJAX Feed API that permits developers to embed data from a cached RSS feed in their websites. The new Feed API allows you to put a bit of javascript on your website - which will then automatically display the contents of an RSS feed. That's great, but it's not quite what I'm after. As I want to do this from a ruby/perl script, and not from within a javascript webpage.

Niall Kennedy reverse engineered the API a bit, and figured out how to get a JSON encoded version of a cached RSS feed from Google's servers. When Niall first started looking into the guts of the Reader and its APIs late last year, members of the Google Reader development team left comments on his blog commending him on his reverse engineering, and provided key bits of information. Thus, while the release of this information isn't 100% sanctioned by Google, its fair to assume that Google is aware it is out there. Most importantly, this method uses the API (and requires an API key that you can request from Google) - which means that in using it, I'm safer and more legit.

Thus, I whipped up a ruby script that will parse the JSON output from Google, and give you a real RSS feed. A live demo, and source code of the RSS/XML cache fetcher can be downloaded here.

Why is this useful? It means that you can scrape someone's RSS/XML feed without ever going to their website. While I'm no lawyer (and this is certainly not legal advice) - I'd imagine that it'd be fairly difficult for anyone to attempt a trespass to chattel claim, since they'll be unable to prove any harm, or consumption of resources.

Google has millions of customers. It's quite likely that their bot is already crawling most popular RSS feeds. Thus, it's very very unlikely that by pulling up a copy of the feed, that you'll cause Google to go and fetch a new copy.

Many websites already provide different (unpassword protected) data to Google than they do to anyone else visting their site. It may be possible, by using Google's RSS cache, to take advantage of this architecture flaw/design decision, and access data that one wouldn't normally be able to get.

Finally, since you won't be hitting anyone's webservers, there is no link (at least in their weblogs) between you and them. They have no way of knowing how often you're accessing their feed. You're hidden amongst the millions of Google users.

Wednesday, May 30, 2007

A Remote Vulnerability in Firefox Extensions

See a demo of the attack against Google Browser Sync: (12MB Quicktime).

Executive Summary

A vulnerability exists in the upgrade mechanism used by a number of high profile Firefox extensions. These include Google Toolbar, Google Browser Sync, Yahoo Toolbar, Del.icio.us Extension, Facebook Toolbar, AOL Toolbar, Ask.com Toolbar, LinkedIn Browser Toolbar, Netcraft Anti-Phishing Toolbar, PhishTank SiteChecker and a number of others, mainly commercial extensions.

Users of the Google Pack suite of software are most likely vulnerable, as this includes the Google Toolbar for Firefox.

The latest version of all of these listed, and many other extensions are vulnerable. This is not restricted to a specific version of Firefox.

Users are vulnerable and are at risk of an attacker silently installing malicious software on their computers. This possibility exists whenever the user cannot trust their domain name server (DNS) or network connection. Examples of this include public wireless networks, and users connected to compromised home routers.

The vast majority of the open source/hobbyist made Firefox extensions - those that are hosted at https://addons.mozilla.org - are not vulnerable to this attack. Users of popular Firefox extensions such as NoScript, Greasemonkey, and AdBlock Plus have nothing to worry about.

In addition to notifying the Firefox Security Team, some of the most high-profile vulnerable software vendors (Google, Yahoo, and Facebook) were notified 45 days ago, although none have yet released a fix. The number of vulnerable extensions is more lengthy than those listed in this document. Until vendors have fixed the problems, users should remove/disable all Firefox extensions except those that they are sure they have downloaded from the official Firefox Add-ons website (https://addons.mozilla.org). If in doubt, delete the extension, and then download it again from a safe place.

In Firefox, this can be done by going to Tools->Add-ons. Select the individual extensions, and then click on the uninstall button.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Who is at risk?

A: Anyone who has installed the Firefox Web Browser and one or more vulnerable extensions. These include, but are not limited to: Google Toolbar, Google Browser Sync, Yahoo Toolbar, Del.icio.us Extension, Facebook Toolbar, AOL Toolbar, Ask.com Toolbar, LinkedIn Browser Toolbar, Netcraft Anti-Phishing Toolbar, PhishTank SiteChecker.

Q: How many people are at risk?

A: Millions. Exact numbers for each toolbar/extension are not released by the vendors. Google Toolbar, which is one of the most popular of the vulnerable extensions, is installed as part of the download process with WinZip, RealNetworks' Real Player and Adobe's Shockwave. Google publicly pays website publishers $1 for each copy of Firefox + Google Toolbar that customers download and install through a publisher's website.

Google confirmed in 2005 that their toolbar product's user base was "in the millions". Given the number of distribution deals that have been signed, the number of users can only have grown in size since.

Q: When am I at risk?

A: When you use a public wireless network, an untrusted Internet connection, or a wireless home router with the default password set.

Q: What can happen to me?

A: An attacker can covertly install malicious software that will run within your web browser. Such software could spy on the you, hijack e-banking sessions, steal emails, send email spam and a number of other nasty tasks.

Q: What can I do to reduce my risk?

A: Users with wireless home routers should change their password to something other than the default.

Until the vendors release secure updates to their software, users should remove or disable all Firefox extensions and toolbars. Only those that have been downloaded from the official Firefox Add-Ons page are safe.

In Firefox, this can be done by going to the Tools menu and choose the Add-ons item. Select the individual extensions, and then click on the uninstall button.

Q: Why is this attack possible?

A: The problem stems from design flaws, false assumptions, and a lack of solid developer documentation instructing extension authors on the best way to secure their code.

The nature of the vulnerability described in this report is technical, but its impact can be limited by appropriate user configuration. This shows the relation between the technical and social aspects of security. For numerous other examples, please see the publications listed at www.stop-phishing.com. It also illustrates the need for good education of typical Internet users. This has been recognized as a difficult problem to tackle, but some recent efforts, e.g., www.SecurityCartoon.com look promising.

Description Of Vulnerability

The Firefox web browser includes the ability for third parties to release code, known as extensions, that will run within the user's browser. Firefox also includes an upgrade mechanism, enabling the extensions to poll an Internet server, looking for updates. If an update is available, the extension will typically ask the user if they wish to upgrade, and then will download and install the new code.

An exploitable vulnerability exists in the upgrade mechanism used by Firefox. The only real way to secure the upgrade path is for those websites hosting extensions and their updates to use SSL technology. The Mozilla team have provided a free hosting service for open source extensions, which is secure out of the box, by having the code served from https://addons.mozilla.org

For the most part, any extension which gets updates from a website that looks like http://www.example.com is insecure, while an extension that gets its updates from a website that looks like https://www.other-example.com is secure.

The vulnerability is made possible through the use of a man in the middle attack, a fairly old computer security technique. Essentially, an attacker must somehow convince your machine that he is really the update server for one or more of your extensions, and then the Firefox browser will download and install the malicious update without alerting the user to the fact that anything is wrong. While Firefox does at least prompt the user when updates are available, some commercial extensions (including those made by Google) have disabled this, and thus silently update their extensions without giving the user any say in the matter.

A DNS based man in the middle attack will not work against a SSL enabled webserver. This is because SSL certificates certify an association between a specific domain name and an ip address. An attempted man in the middle attack against a SSL enabled Firefox update server will result in the browser rejecting the connection to the masquerading update server, as the ip address in the SSL certificate, and the ip address returned by the DNS server will not match.

When Are Users Vulnerable

Users are most vulnerable to this attack when they cannot trust their domain name server. Examples of such a situation include:

- Using a public or unencrypted wireless network.

- Using a network router (wireless or wired) at home that has been infected/hacked through a drive by pharming attack. This particular risk can be heavily reduced by changing the default password on your home router.

- Using a 'network hub' - either at the office, a university, or elsewhere.

Using this vulnerability, an attacker can force a user's browser to download and install malicious code. Such code runs within the browser, and does not run as a superuser or privileged user. A malicious extension could spy on the user, perform an active man in the middle attack on e-banking sessions, steal emails, send spam from the user's account, perform local network port scanning, and a number of other nasty tasks.

Fixing The Problem

The number of vulnerable extensions is more lengthy than those listed in this document. Until vendors have fixed the problems, users should remove/disable all Firefox extensions except those that they are sure they have downloaded from the official Firefox Add-ons website (https://addons.mozilla.org). If in doubt, delete the extension, and then download it again from a safe place.

In Firefox, this can be done by going to Tools->Add-ons. Select the individual extensions, and then click on the uninstall button.

The vendors can either host their extensions on https://addons.mozilla.org, or if they choose to host them on their own webservers, they should turn on SSL. While this is not a particularly difficult engineering effort, for those extensions with millions of users, it may require a few additional machines to cope with the extra load required by all of those SSL connections.

As a matter of general policy, vendors really should not have their software silently install updates without asking the user's permission. It is asking for trouble.

The Mozilla Security Team has updated their developer documentation to properly address the risks that hosting updates from an insecure server can pose. The updated documentation can be found online.

There seems to be one commercial vendor whose extension does get its updates from a secure website. The McAfee SiteAdvisor does things correctly, and is thus not vulnerable to this attack.

Why Are Commercial Vendors' Extensions Vulnerable

The vast majority of commercial software vendors do not have their extensions hosted on the https://addons.mozilla.org website. They prefer to control the entire user experience, and thus wish to have the users connect to their own servers for the initial download and future updates. These vendors are not hosting the updates on a secure, SSL-enabled webserver, and thus the update process for these extensions is vulnerable to a man in the middle attack.

Some vendors have made things much worse by having their extensions automatically update without asking the user for permission. The majority of the open source extensions follow the Firefox defaults, and thus require that the user "OK" any software updates.

What About Code Signing

The code signing functionality in Firefox is fairly limited. The main difference is that a signed extension will show the signer's name when the user is prompted to install the extension, while an unsigned extension will list "un-signed" next to the extension name.

The availability of an update without signatures for extensions that previously had a valid signature does not raise any kind of error. Furthermore, the signature is thrown away as soon as the new extension update is installed.

Code signing is not currently an effective method of securing the extension upgrade path. Developers should instead have their updates served by a SSL enabled webserver.

Notification of Vendors

The Mozilla Security Team was notified of this on April 16th. They do not believe that this is a Firefox bug or vulnerability, due to the fact that the vast majority of extensions (those hosted at https://addons.mozilla.org) are secure by default.

The Ebay developed, but Mozilla cobranded Firefox/Ebay extension was vulnerable, but the Mozilla Security Team fixed the problems and rolled out an update within 2 days of being notified.

The Mozilla developers have created an entry in their bug tracking database for the insecure updates issue, but it is not slated to be fixed until Firefox 3.0.

The Google Security Team was notified of the problem on April 16th. They were given a full explanation of the vulnerability. An additional four emails were sent between April 20th and May 24th. These included additional information on the problem, offers to provide help as well as offers to delay publication of the vulnerability. The Google Security Team replied on May 25th stating that they were working on a fix, and expected to have it ready and deployed before May 30th. At the time of publishing this vulnerability disclosure, it does not appear that Google has rolled out an update yet.

The Yahoo Security Team was notified of the problem on April 21st. A human being replied to the initial report with intelligent questions, in less than 12 hours, on a Saturday. There has been no further communication from Yahoo.

The Facebook Security Team was notified on April 21st. They replied with two emails from a human being confirming receipt of the report. There has been no further communication from Facebook.

The number of vulnerable extensions continues to grow. It is just not feasible to provide advanced notification to every creator of a Firefox extension. Advanced notice has thus been given to those major vendors who the research initially focused on.

The CERT disclosure policy states that "All vulnerabilities reported to the CERT/CC will be disclosed to the public 45 days after the initial report, regardless of the existence or availability of patches or workarounds from affected vendors." Given the fact that fixing the flaw is a fairly trivial engineering task (changing a couple urls from http->https), and it is very easy for users to protect themselves (remove the vulnerable toolbars), sitting on this information any longer would be a bad idea.

Another other well respected responsible disclosure policy sets a 5 days time limit. If the vendor does not keep in touch with the security developer every 5 days, then the vulnerability will be made public. While this path was not followed, it is worth noting that neither Google, Yahoo or Facebook made an attempt to keep the lines of communication open. Following such a policy, this information would have thus been revealed a number of weeks ago.

Self Disclosure/Conflict of Interest Statement

Christopher Soghoian is a PhD student in the School of Informatics at Indiana University. He is a member of the Stop Phishing Research Group. His research is focused in the areas of phishing, click-fraud, search privacy and airport security. He has worked an intern with Google, Apple, IBM and Cybertrust. He is the co-inventor of several pending patents in the areas of mobile authentication, anti-phishing, and virtual machine defense against viruses. His website is http://www.dubfire.net/chris/ and he blogs regularly at http://paranoia.dubfire.net

This vulnerability was discovered and disclosed to vendors during the spring semester, while he was paid as a researcher assistant at Indiana University. He is now currently working at an internship in Europe. This disclosure announcement, and the vulnerability in no way reflect the opinions or corporate policy of his current employer nor those of Indiana University.

Information on this vulnerability was disclosed for free to the above listed vendors. Christopher Soghoian has not been financially compensated for this work. He has no malicious or ill feelings towards any of the vulnerable software companies.

He was an intern with the Application Security Team at Google during the summer of 2006. Finding this vulnerability did not involve using any confidential information that he learned while employed by Google. It was done solely with a copy of Firefox and a packet sniffer.