This blog post is likely to be the last until September, as I'll be leaving Munich next week, and will spend the entire month of August backpacking in India. I expect to have email access in Ladakh, and I doubt if there will be decent Internet in the remote villages in the Parvati Valley - at least, there wasn't any when I visited last year.

Today's blog post is in three parts, all related to airport security: The end of my legal troubles, the successful publication of my airport security research paper, and a brief writeup of my recent experience going through British airport security.

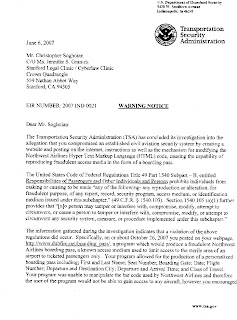

I received word from my awesome pro-bono legal counsel, Jennifer Granick, that TSA has wrapped up their investigation, and will not be filing civil charges against me. The FBI dropped their investigation in November last year. It looks like the entire affair is now over.

Ten months after the FBI strong-armed my ISP into taking down my website (as well as ransacking my home, and making off with my computers and passports), the flaws that I highlighted are still exploitable, and have not been fixed. The reimplementation of my boarding pass generator by "John Adams" (that was first released on November 1 2006) also remains online.

In addition to the help of super-lawyers Jennifer Granick and Steve Braga, I received an outpouring of support from around the world, from the students, faculty and staff at Indiana University, and from my friends, family and loved ones.

One particular friend provided me with a place to stay the night the FBI visited, and had it not been for their instance that I come with them, I would have been at home when the G-Men broke in at 2AM, guns drawn. To this person in particular as well as everyone else who helped out, I am eternally grateful.

Security research is typically a two part process: You break something, and then you fix it. My boarding pass generator and numerous blog-posts highlighting the no-id + no-fly list problem were the first part of the research process. A newly released academic paper fixing the flaws is the second part.

I am proud to announce that my paper "Insecure Flight: Broken Boarding Passes and Ineffective Terrorist Watch Lists" has been accepted for publication by the IDMAN 07 working conference, where I'll also be presenting it in Rotterdam, Netherlands in October.

Bruce Schneier, Senator Schumer, and others did a great job in highlighting the fake/modifiable boarding pass problem years before I built my hullabaloo causing website. However, no academic has yet written about this. My paper fully explores the interesting combination of the ability to fly without ID, and the government's insistence on maintaining a no-fly list. I have personally flown without ID over 12 times, and I do not believe that anyone else has really written about the fact that this essentially neutralizes the no-fly list. I also present a new physical denial of service attack against the TSA passenger screening system.

It is important to note that I do not take a position on the no-fly list in the paper. The US government has spent over $250 million dollars on implementing the list. The paper thus explores methods to effectively enforce it. The paper presents a technical solution to the problem (digitally signed boarding passes), which will enable TSA staff to instantly learn if a pass is valid or not, or if it has been tampered with, as well as stopping all other known attacks.

Were the airlines in the US willing to check the ID of each passenger before they board a flight - something they did right after 9/11 - my technical solution wouldn't be necessary. 100% effective enforcement of the no-fly list is only possible when airlines check all IDs at the gate, and when the US government takes away our right to fly without ID.

A pre-publication copy of my paper can be downloaded here.

I was in London two weeks ago to see family. I flew in a few hours after the failed bomb attack, and was watching TV in east London when the idiots tried to drive a flaming jeep into Glasgow airport.

I flew back to Germany a couple days later, and in spite of the fact that I had to get up at 4AM for my flight, I paid close attention to the security procedures in place at Stansted Airport.

- There is now an unwritten but enforced rule banning large umbrellas. If it can't fit in a carry on bag, you're forbidden to take it through security. British airport security staff thus seized my golf-umbrella.

- Just as in the US, the British consider hummus to be a liquid. I took the top off the container, held it upside down, thus demonstrating that it would not pour out, but the screener insisted that I give it up. The supervisor on duty did at least let me sit on one of the bag-searching tables, with people's bags being searched on both sides of me. Thus, under the watchful corner-of-the-eye of her security staff, I ate all the hummus and pita bread I had brought with me as my lunch. The supervisor even went out of her way to bring me an unrequested cup of water . I can't imagine TSA staff doing this.

- Print at home boarding passes with the airline Easyjet contain a computer-readable barcode. This barcode is read by airport security screening staff, before you even enter the metal detector/x-ray line. I'm not sure what happens if the barcode doesn't find a match - but I did observe that my name came up on the screen, which the security staff member then compared to my ID. This means that if your name is not associated with a paid ticket in the reservation system, you will not even gain access to the security screening area. Quite impressive.

- Once Easyjet staff began boarding, they looked up every passenger's name in the reservation system and checked it against an ID before letting the passenger onto the airplane. No passport, no entry.

Comparing US domestic flight security to European flight is not 100% fair. You do not need to show ID to travel within the US, and except for a few select situations, you cannot be forced to show ID in the US. Europeans do not have this right, and as the individual European countries are much smaller than the US, you are essentially always crossing some international border when you fly.

US airlines somehow managed to get the government to let them stop asking for ID at the gate - after they complained about the labor costs and delays the process introduced to the flight-boarding process.

Nonsense.

If Easyjet, a no-frills airline that won't even give you a free glass of water, can ask passengers for ID and somehow manage to turn a profit, as well as get their flights off in a reasonable amount of time, then the US airlines are not telling the truth.

I lived in the UK when the IRA, through the use of bombs placed in train-station rubbish bins, forced the authorities to remove every trash can from train and tube-stations in London.

While the Israelis get a lot of credit for their airport security skills - as others have pointed out before me, Israel is small, and doesn't have many flights in or out. London's Heathrow is one of, if not the the busiest airport in the world. The British have had this airport security thing figured out for years. If the US government is serious about enforcing the no-fly list, they should learn a thing or two from the Brits, and force all airlines to check passengers' ID against a computerized reservation system record at the gate.

The flip side of course, is that if the US government finally accepts that the no-fly list is a pointless waste of money, then that money can be spent on more important things - like training TSA staff to actually find the weapons and bombs that currently seem to miss, again and again.